A new climate strategy is gaining ground among companies to achieve their climate goals: insetting. This means offsetting or reducing CO₂ emissions within a company’s own value chain. This can replace investing in external reduction projects, offsetting: that compensating or reducing place outside company’s own supply chain. For example through tree planting or mangrove restoration elsewhere.

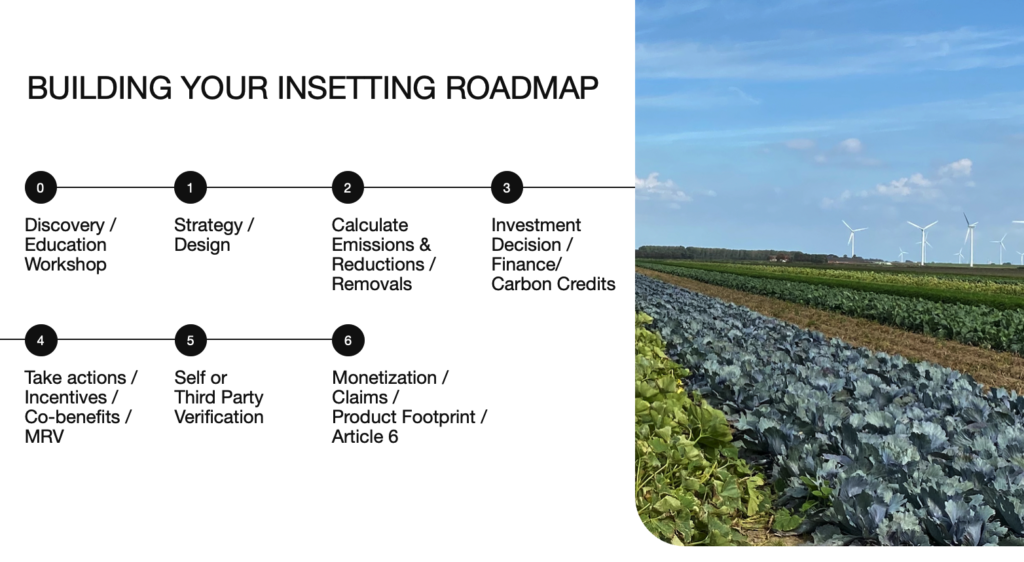

With insetting I help companies organise reporting reductions and carbon removals in a robust way, apply a rewarding scheme, ensure the chain of custody is properly organized, how to claim against corporate climate targets and lower the product carbon footprint and comply with green claims regulations.

Insetting adds value to the company’s own supply chain. Companies like IKEA, Nestlé, Friesland Campina, Pepsico, and Arla are engaged in insetting. Global support against tropical deforestation and for mangrove protection, finance by offsetting remains important, of course. But to achieve their own reductions, companies are increasingly staying closer to home.

This is partly because companies want to avoid potential criticism of the use of offsetting. Negative stories about several CO₂ projects have recently appeared in the media. Another reason is that companies want to make their own supply chains and agriculture more resilient to flooding or drought, or to energy supply and logistics problems caused by climate change.

Insetting is not automatically easier or cheaper. You need to understand the supply chain and establish primary emissions data, ensure a robust chain of custody and then make agreements with the supply chain partners, regarding interventions and for example reward farmers and invest in more resilient farms

Scope 3

Supply chain emissions are included in the framework of companies’ emissions reporting. These are called “scope 3” emissions. A company has scope 1 emissions, the direct emissions of its own factory, for example, and scope 2, the indirect emissions from purchasing electricity and heat. Scope 3 emissions are indirect emissions that are necessary for a product (e.g., agricultural emissions for milk) or that result from the use of a sold product (e.g., a cargo flight, truck emissions, or electricity for roasting coffee). A company’s scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions can easily account for 90% of its total emissions, and according to Deloitte research, only 15% of companies report these emissions.

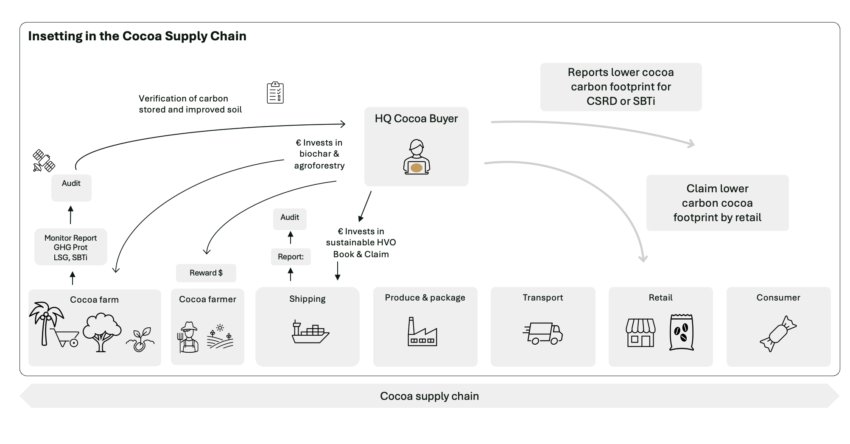

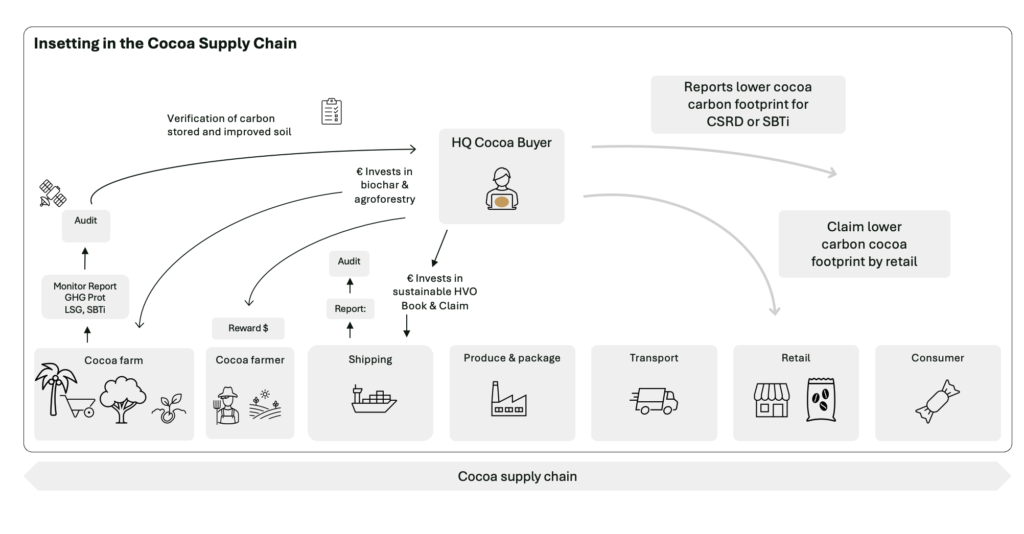

When implementing insetting, one can learn from the experience with CO2 projects for offsetting: for establishing the baseline and monitoring and verifying CO2 reductions and carbon storage in soil, for example. Because even though insetting does not require applying for CO2 certificates from a carbon credit program, and there is no trading of certificates, companies investing in insetting must be transparent about the projects. And the CO2 reductions must be validated so they can be claimed and deducted from a company’s climate objectives. See the coffee chain example in the figure.

European Regulations

- The European reporting regulations for companies (EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive ‘CSRD’) already require the largest companies to map the climate impact on their own supply chains and to take measures within the supply chain to contribute to European climate objectives. Companies are permitted to offset the remaining ‘hard to abate’ emissions with offsets, specifically through carbon credits for carbon sequestration.

- At the end of December 2024, the EU established a certification framework for permanent carbon removals, carbon land management, and carbon storage in products (CRCF), which also contribute to climate objectives. The European Commission indicates that companies can also use these removal certificates to determine carbon sequestration in their supply chains.

- From 2028 onward, emissions from fossil fuel use in transport and buildings will fall under the EU ETS-2. In fact, This means a large part of Scope 3 of the oil and gas sector is subject to a CO2 obligation, and CO2 emissions must reach zero by 2044. Companies can refer to their emission reports to specify their chain emissions and the policies they apply.

Innovative Insetting Concepts

- Because products sometimes consist of multiple raw materials and ingredients—think of dairy or food products where various products are used, often it is unknown which farmer the ingredients originate from—so-called market-based solutions such as supply shed approaches have been developed. In these approaches, financing scope-3 reductions or removals focus on regional or landscape-specific interventions and on encouraging deforestation-free and regenerative agriculture in a region. Such an approach is acceptable if supported by clear impact data and independent verification.

- Because supply of sustainable fuels for aviation and shipping are limited, book-and-claim systems are being used, where certificates are kept in registries. This is considered credible as an insetting approach if linked to robust tracking systems, such as SAF certificates. GoodShipping and the Port of Rotterdam Authority are using ‘Switch to Zero’. Setting the stage for sustainable maritime transport.

With these types of innovative market strategies, potential “double counting” must be avoided through clear agreements and independent verification and transparent reporting according to the guidelines established by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG), the Science Based Targets Initiative, ISO standards for determining carbon footprints, and carbon credit standards. SBTi and the GHG Protocol are reluctant to accept the book-and-claim system for scope 3.

Categories of companies that can be helped with insetting:

- Coffee (see image) or chocolate producer, or a clothing brand, can invest in sustainable agricultural practices, such as biochar or agro-forestry among farmers, so that additional trees are planted on the farms to capture CO₂ or they use more solar energy. See also the example of PepsiCo and Yara, which achieve reductions with fertilizers; and H&M cooperating with WWF on regenerative cotton plantations in India.

- Soft drink and beer producers can invest in returning water to nature (Coca-cola) or bring cleaned waste-water back in soils and of farmland (Swinkels).

- Dairy products company helps farmers reduce methane emissions through more sustainable animal feed, manure digestion, and manure processing and carbon farming and regenerative practices

- Car manufacturer invests in recycling programs for metals and batteries within its own supply chain or in recycling tires for car coatings (Volvo deal with SSAB)

- Cosmetics and Essential Oil brands promote regenerative farming or help suppliers replace plastic packaging with compostable alternatives;

- A wind farm builder encourages suppliers to use biofuels in ships or electric trucks. Or he can ensure the complex recycling of old wind turbine blades in polymers or train sleepers (Eneco with CRC).

- The building sector can decarbonize its supply chain, and build with a lower carbon footprint by using natural fibres, rewarding farmers ad storing biobased recyled of direct air carbon in buildings, also supported by EUs carbon removal certification in buildings.

Who and which country can claim the benefits of insetting?

The CO₂ reduction and other benefits of insetting can be claimed by:

- The company that made the investment or owns the emissions and reports according to standards and has the results externally verified by an auditor. For example, a milk supplier cannot claim the reduction for its target if the milk cooperative that made the investment has already done so (otherwise, double counting occurs). The milk does, of course, have a lower carbon footprint, which can be stated on the packaging.

- If two companies collaborate in a supply chain, they can also decide to jointly claim the reduction or agree to have the reduction claimed by a single company. The reporting, validation, and agreed-upon claims must be published transparently.

- Insetting involving 2 countries: in interesting option is to add an agreed portion of the reductions, financed for example by Dutch companies in their foreign supply chain to the Dutch national emissions report. The Netherlands could agree with Ghana or Colombia, to transfer part of the additional carbon sequestration on cocoa or coffee plantations to The Netherlands as so-called ITMOs (Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes). This is permitted under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. This allows the Netherlands and Dutch companies to contribute to affordable additional reductions for the NDC through international insetting.

Insetting is therefore not automatically easier or cheaper. You need to understand the supply chain and establish primary emissions data, and then make agreements with the supply chain partners regarding measures. Farmers should also be rewarded for making their supply chains more sustainable. But because the supply chain becomes more sustainable, and there are co-benefits for both farmers and nature, the value of the supply chain increases and the risks of climate damage are reduced. That is why a growing number of companies are choosing this approach.

Insetting consultancy

Companies can be helped how to ensure their chain of custody is properly organized and that reporting on carbon reductions or storage is robust. It also is necessary to ensure that reductions and removals can be claimed against corporate targets (SBTi, CSRD) and that claims on consumer products comply with the EU Empowering Consumers for the Green Transition directive and the future Green Claims Directive.